Measuring Progress in Negotiations – Why it is vital

Spring 2018 – Tactical Edge – https://www.ntoa.org/tacticaledge/

Background

Since the introduction in the 1970’s of negotiation as a tactical option in law enforcement responding to crisis and hostage incidents, it has been vital to understand how to measure progress in negotiations as it greatly influences the decision making process of command and that of other tactical options.

1972 saw Black September terrorists took eleven Israeli Olympic athletes hostage at the Munich Games. The traditional confrontational police response resulted in the death of the athletes, a police officer and ten terrorists; this event, along with others fuelled concern about the loss of life in hostage incidents.

Motivated, the New York Police Department, utilizing the talents of Harvey Schlossberg, a detective with a PhD in psychology and Lieutenant Frank Boltz, they developed tactics that led to the resolution of high conflict incidents without the loss of life, emphasizing the importance of:

- Containing and negotiating with the hostage taker and

- Understanding the hostage taker’s motivation and personality in a hostage incident;

- Slowing an incident down so that time can work for the negotiator.

January 19th, 1973 four armed robbers entering Al’s Sporting Good Store threatening employees and customers with sawn off shotguns and handguns were soon shot at by the attending officers injuring one of the perpetrators. Rather than storming the store officers began to negotiate successfully getting a hostage released to talk to police. Demands for a doctor to tend to their wounded companion were met and another hostage was released. Portraying as Black Muslims, several Muslim clergy were allowed to talk to the perpetrators to establish good dialogue through the use of provided walkie-talkies. Sporadic gunfire occurred throughout the incident and eventually the remaining hostages escaped. Without their hostages, the perpetrators had lost their bargaining power and were convinced by negotiators that to continue to fight for the oppressed minorities they must first stay alive. The motto of the NYPD Hostage Negotiation Team remains ‘Talk to Me’.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation designed, developed and launched their Hostage Negotiation training program at the FBI Academy in Quantico, the same year, thus making negotiation a legitimate law enforcement strategy for critical hostage incidents and went onto form the framework and foundation for hostage negotiator training worldwide that lasts to this day.

Contain and Negotiate Strategy

“Contain and negotiate” has since been adopted as the primary strategy in the initial response to hostage siege, but it is a strategy that must be continually and robustly evaluated to measure its effectiveness. Not every siege is the same; they are all unique because we are dealing with human beings.

Hostage negotiation uses an array of proven communication techniques to engage the hostage taker in direct dialogue, so that you may influence and ultimately change his/her behavior towards a peaceful resolution.

It is not a wait and see option, but a real option that de-escalates tension, gathers vital intelligence, reassures hostages held and ultimately works to influence and change the actions of the hostage taker towards a peaceful resolution whilst commanders can consider other tactical options.

Behavioral Change Stairway

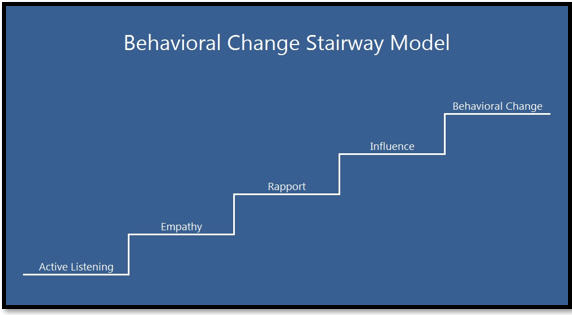

Based on evidence from social research, the FBI developed the Behavioral Change Stairway Model as a means of visually demonstrating the various steps to be taken in influencing and changing the behavior of the perpetrator:

Likened to climbing stairs, you know when you are making progress as you go from the bottom of the stair to the top. Similarly, it is vital during negotiations and dialogue with the perpetrator that you can measure your progress on the model above.

To measure the effectiveness of any ‘contain and negotiate’ strategy negotiators must be able to measure progress towards the ultimate goal of a peaceful resolution. Negotiators must take robust evaluation and assessment of where they are in negotiations and what they had not achieved in line with their strategy. Failing to do so, impacts on tactical negotiator advice to the various levels of command, and the review of the ‘contain and negotiate’ strategy.

Measures of Progress

Through the analysis of case studies, it has been identified that progress in negotiations can be measured through the some of the following actions:

- Emotional outbursts are declining and conversations are getting longer

- Perpetrator is in dialogue and sharing information of a personal nature and that of his/her motivations that have led to this action

- Hostages are released

- Weapons are surrendered

- Absence of physical injury to hostages

- The incident is static

- A routine has been established

It is important to recognise that no list can be definitive and exhaustive, as there are a multitude of factors that may influence the behaviour of a hostage taker and/or hostages. We will now explain these in more detail.

Emotional outbursts declining

Hostage situations are highly emotionally driven situations that frequently have people releasing those emotions in their language. As negotiators, we know that this includes language that can include threats, profanity, as well as other aggressive language. An effective negotiator allows the subject to vent their emotions. The initial contact with the subject is often laced with emotional outbursts. One of the first indications of progress in negotiations is the decline of these outbursts over time.

Perpetrator in sharing dialogue

This is where the importance of using active listening to create rapport and trust comes into play. Active listening and empathy builds rapport and can lead to some level of trust that can allow the suspect to open up, sharing information, and providing insight behind the reasons of their actions. The majority of hostage taking events are un-planned, with hostages being taken because of a subject experiencing a highly emotional event and acting on raw emotion rather than rational thinking. Getting the suspect to share his/her story helps provide the negotiators with insight the suspects perception of the event.

Release of hostages

Obviously one of the most significant signs of progress is the release of hostages. Although the release of one or all hostages does not guarantee that the suspect will comply with instructions and surrender, it does in most cases at a minimum give a significant indication that the suspect is open to coming out.

Weapons surrendered

Next to the release of hostages, the act of surrendering weapons is the most positive sign of progress. Although a very positive indication we must always assume the suspect has at least one weapon until he/she untenably comes out and submits to custody. In some instances, involving a single hostage, ammunition or weapons may be exchanged for food and other comfort items.

Absence of physical injury to hostages

An encouraging sign of progress is the absence of physical injury to the hostages, albeit any injury that took place prior to negotiator contact should probably not be considered. In situations where the hostage is an object of anger to the hostage taker, and the hostage taker not injuring the hostage may be especially promising.

Static incident

A static incident is indicated when for a significant period, the suspect is neither escalating in emotions or hostility nor deescalating. A static incident may still be considered an indication or progress if the suspect had spent a significant amount of time in a heightened agitated state and the mood, including hostages within the stronghold has become stable.

Established routine

As humans we tend to follow established routines, for example, eating, sleeping, going to the rest room, etc. and this becomes more prevalent over an extended period. Observing this can be considered progress because the suspect and hostage(s) generally must be in some form of a non-extreme crisis state to develop a pattern. Behavioural patterns within the stronghold are particularly useful in considering tactical intervention.

Recording progress

Whilst it is essential to make progress in negotiations to achieve a peaceful resolution, it is also vitally important to record that progress and how it influences command decisions on the viability of the ‘contain and negotiate’ strategy. This is especially important given the rise of litigation in families pursuing claims following the death of loved ones in a hostage siege.

Law enforcement and military response to hostage sieges have been subject to judicial inquiry where there is a responsibility upon the State to investigate the actions of authorities in response to hostage sieges resulting in the loss of life:

Downs -v- USA

October 4th 1971 an armed George Giffe and his accomplice Bobby Wayne Wallace hijacked an aircraft and demanded the pilots fly to the Bahamas with his Giffe’s estranged wife as a hostage. Landing at Jacksonville Airport to refuel, the subsequent response and actions of the FBI responding to the incident led to Giffe murdering his estranged wife and the remaining pilot, Brent Q. Downs before fatally injuring himself.

Down’s widow filed a lawsuit against the FBI in the Federal Tort Claims Act to allegations of negligence on the part of crisis negotiators that had resulted in the death of her husband. The Court indicated that the standard approach of extending the negotiation process would have been much more appropriate; that special circumstances mandate specialized preparation and responses in terms of personnel selection, training, assignment, and equipment and that a higher level of performance expectation is placed upon personnel who have received specialized training and who may possess a higher level of relevant experience.

The incident was a glaring example of everything not to do in a hostage event and as the legal foundation upon which law enforcement negotiations have continued to develop and improve.

Tagayeva and Others -v- Russia

September 2004, a terrorist attack on a school in Beslan, North Ossetia (Russia), where for or over fifty hours heavily armed terrorists held captive over 1,000 people, the majority of them children. Following explosions, fire and an armed intervention, over 330 people lost their lives (including over 180 children) and over 750 people were injured.

In the case of Tagayeva and Others v. Russia, brought by 409 Russian nationals who had either been taken hostage and/or injured in the incident, or are family members of those taken hostage, killed or injured; the European Court of Human Rights made the following findings.

Unanimously, the Court held that there had been a violation of Article 2 (right to life) of the European Convention on Human Rights, arising from a failure to take preventive measures. The authorities had been in possession of sufficiently specific information of a planned terrorist attack in the area, linked to an educational institution. Nevertheless, not enough had been done to disrupt the terrorists meeting and preparing; insufficient steps had been taken to prevent them travelling on the day of the attack; security at the school had not been increased; and neither the school nor the public had been warned of the threat.

Unanimously, the Court found that there had been a violation of the procedural obligation under Article 2, primarily because the investigation had not been capable of leading to a determination of whether the force used by the State agents had or had not been justified in the circumstances.

The Court held that there had been a further violation of Article 2, due to serious shortcomings in the planning and control of the security operation. The command structure of the operation had suffered from a lack of formal leadership, resulting in serious flaws in decision- making and coordination with other relevant agencies. They also found that there had been a violation of Article 2 arising from the use of lethal force by security forces. In the absence of proper legal rules, powerful weapons such as tank cannon, grenade launchers and flame-throwers had been used on the school. This had contributed to the casualties among the hostages and had not been compatible with the requirement under Article 2 that lethal force be used “no more than [is] absolutely necessary.”

Lindt Café Siege Inquest, Sydney, Australia

December 2014, a lone gunman, Man Haron Monis, held hostage ten customers and eight employees of a Lindt Chocolate Café located at Martin Place, Sydney, Australia.

The siege led to a 16-hour standoff, after which a gunshot was heard from inside and police officers from the Tactical Operations Unit stormed the café. Hostage Tori Johnson was executed by Monis and hostage Katrina Dawson was killed by a police bullet ricochet in the subsequent raid. Monis was also killed. Three other hostages and a police officer were injured by police gunfire during the raid.

Police were criticised over their handling of the siege for not taking proactive action earlier, for the deaths of hostages at the end of the siege, and for the lack of negotiation during the siege. Hostage Marcia Mikhael called radio station 2GB during the siege and said, “They have not negotiated, they’ve done nothing. They have left us here to die.”

Early on, hostages were seen holding an Islamic black flag up against the window of the café, featuring the shahādah creed, which was initially mistaken by some media organisations as the flag used by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant(ISIL); Monis later demanded that an ISIL flag be brought to him. He also unsuccessfully demanded to speak to the Prime Minister of Australia, Tony Abbott, live on radio. Monis, described by Abbott as having indicated a “political motivation” but the eventual assessment was that the gunman was “a very unusual case—a rare mix of extremism, mental health problems and plain criminality”.

The subsequent coronial inquest published its findings for New South Wales Police Force, specifically on dealing with negotiators’ attempts to engage with Monis; their responses to his demands, and their assessment of progress demonstrate deficiencies in current practice. To respond to those deficiencies, recommended that they conduct a general review of the training afforded to negotiators and the means by which they are assessed and accredited. Specifically, the review should consider the training provided regarding:

• Measuring progress in negotiations;

• Recording of information, including the systems by which that occurs;

• The use of third-party intermediaries;

• Additional approaches to securing direct contact with a person of interest; and

• Handovers.

To develop a cadre of counterterrorist negotiators and provide them with appropriate training to equip them to respond to a terrorist siege and to develop policies that require the recording of negotiation strategies and tactics, demands made by a hostage taker, and any progress towards resolution (or lack thereof) in a form readily accessible by commanders and negotiators.

Conclusion

In the increasing world of law enforcement accountability, scrutiny and the speed of instant media a legion of armchair critics has developed, some of whom are only to willing to condemn police tactics publically with the benefit of hindsight.

Recording and measuring progress in negotiations is essential to allow Commanders to be reassured as to the effectiveness of negotiations or where progress is absent to consider other tactical options often making these critical decisions in a heartbeat.

Few can appreciate and understand the complex human dynamic in such critical events as hostage taking; therefore accurately recording command decisions and all supporting tactical advice, including negotiations, can only benefit the law enforcement community, the affected families and the authorities when it comes to judicial review.

Andrew Brown Mark Lowther